Auto classified revenues appear to be headed to a 10-year low in 2006, with slim chances of an upturn in the future.

Based on the dismal sales of several major newspaper chains in the third quarter, it appears that total automotive classified revenues for the year may tumble to as low as $4 billion, a level last seen in 1996.

Auto sales fell 15% to $1.8 billion in the first half of this year, as compared with $2.1 billion in the same period in 2005, according to the

Newspaper Association of America, the industry-supported trade group.

While total statistics for the third quarter of this year are not yet available, automotive classified revenues in the period fell

10.1% for Gannett, the largest publisher;

12.2% for McClatchy, the No. 2 publisher; 15.7% for Journal Register;

29.1% for Journal Communications, and

30% for Media General.

Based on these results, I have estimated conservatively that auto ad sales will fall a minimum of 10% in each of the third and fourth quarters of this year. At that rate, total annual sales will be $4 billion. Given the velocity of decline in the first nine months, this bleak estimate may prove to be too generous.

Apart from the explosion of help-wanted advertising that accompanied the Bubble between 1995 and 2000, car ads historically have been the biggest contributor to the holy trinity of highly profitable want-ad categories. Real estate, of course, is the third of the trio.

The largest want-ad category as recently as 2004, auto is falling fast. After touching nearly $5.2 billion in 2003, auto ad sales slid to a bit less than $4.6 billion in 2005. If sales drop to $4 billion this year, then roughly 23% of the business will have vaporized in three years. (See chart below.)

Although auto advertising remains among the top three classified revenue producers for most publishers, auto volume now actually trails the “other” category at Journal Register, according to CEO Robert Jelenic, who made the disclosure in a quarterly conference call with investors. The “other” category includes incidental ads for things like garage sales, pets and firewood.

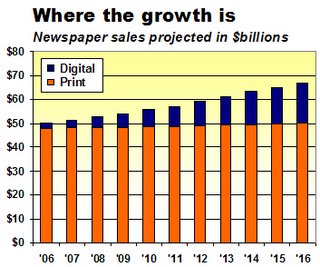

Classified ads of all types collectively contributed 36% of the industry’s $47.4 billion in print sales in 2005 and an equal or greater percentage of its profits. When want-ad sales falter, the industry shudders. And it has had plenty to shudder about since the mid-1990s, given the rise of such low- and no-cost web competitors as Monster, AutoTrader, eBay and Craigslist.

In addition to suffering from the structural shifts caused by the new media, classified ads also are highly sensitive to cycles in the economy. As demonstrated by the record $8.7 billion in recruitment ads purchased in 2000, the business booms when times are good and busts when they aren’t. Emphatically proving this point, $3 billion worth of job ads, or 34.5% of the business, vanished when the Bubble fizzled between 2000 and 2001.

The question regarding the current decline in auto advertising is whether it is structural or cyclical and, thus, whether the downturn is permanent or transient. Unfortunately for publishers, the evidence is growing that the change is structural, making for a negative long-term prognosis.

In addition to competition from online auto sites (including Cars.Com, which was created by several leading publishers to capture some of the web sales lost to print), the structure of the local auto-advertising marketplace is about to be irrevocably altered by a significant contraction in the number of dealers available to buy ads.

In a move expected to be followed by General Motors and Chrysler, Ford wants to cut the number if its dealers by 14% over the next three years to 3,700 from 4,300, says securities analyst Paul Ginnochio of Deutsche Bank. Coming on top of an 11.8% reduction in Ford outlets over the last decade, there will be considerably fewer Ford dealers in your future.

The 18 largest urban areas are targeted for the bulk of Ford's dealer consolidations, which will be especially hard on the metro newspapers challenged by high fixed costs and shrinking revenues. But you can’t blame the

troubled domestic auto makers for wanting to thin their unwieldly dealer networks -- or dealers lining up to take the hefty cash buyouts offered by Detroit to encourage them to go away.

“There are 134 Ford dealers in Southern California, selling an average of 900 cars and trucks a year,”

reported the Los Angeles Times. “Toyota, by comparison, has 75 dealers covering the same territory, each selling about 4,000 vehicles a year.”

In cutting the number of dealerships, Ford and other domestic automakers hope they will improve

profitability for the survivors. If dealers are feeling more flush, that could be a plus for newspapers and the other media, like radio and TV, who covet their ad budgets.

On the other hand, a reduction in dealerships not only will cut the absolute number of potential advertising accounts, but also likely will reduce their perceived need to advertise, since fewer competitors will be trying to sell the same customer the same vehicle. Even if the Toyota dealers in Southern California sell four times as many cars as the average Ford shop, they aren't buying four times more advertising to do so.

In the interests of clinging to an ever larger share of dwindling car-dealer budgets, some newspapers have reduced their mainsheet advertising rates, created standalone auto shoppers and enhanced their websites to include such features as complete, searchable lists of the used-car inventories of participating dealers.

Those steps are headed in the right direction, but newspapers will have to become even more innovative in the future, if they hope to maintain their historic importance as marketing partners for car dealers. One avenue they should pursue is generating targeted leads that help dealers identify specific individuals who are about to buy vehicles or after-market products and services.

While publishers get ready to pop the hood, the hazard lights will be flashing.